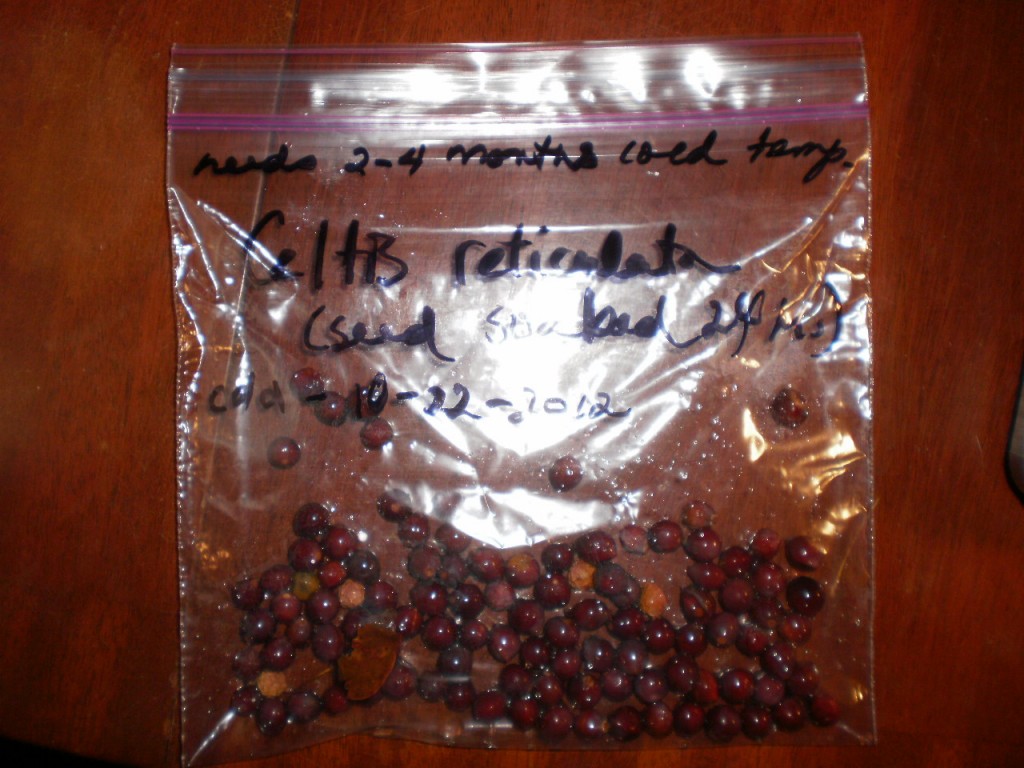

I promised to explain how to germinate hackberry seeds. It’s not too complicated, but it takes a little more planning than tossing marigold seeds out in the spring. In the picture above you can see the seeds we collected last week. These came from the tree growing on the south-facing slope.

Most trees and shrubs, and many perennials, have seeds that need to experience winter before they will germinate. If, for example, you plant a columbine seed on a warm day in June, it will not germinate quickly. It will probably not germinate for over a year, it will just sit in the warm soil until next June. Seeds do this to ensure that they don’t germinate at the wrong time of year. They don’t want to start growing and then find themselves faced with weeks of hot and dry weather. Seeds, even seeds of drought tolerant species, need moisture in their early lives. That’s why you’ll often see a plant like Castilleja integra (Indian Paintbrush) growing near a rock, or in a slight depression, or on a north facing slope–anywhere the seed can find a little more moisture, a little help in getting started.

People in the nursery business want to mimic these winter conditions to trick seed into germinating at our convenience. We don’t want to wait a year or more for a seed to decide conditions are right. What we’ve learned, over the years, is that most perennials need about a month of 40 F. to convince them that winter has passed. To germinate our state flower, Aquilegia caerulea, I put the seeds in a plastic ziploc bag, add a tiny bit of water, just enough to moisten the seeds but not so much that water pools in the corner of the bag, and put it in the refrigerator. Not the freezer, the refrigerator! The seed doesn’t need or want the 0 F. of the freezer. And, it doesn’t work to stick a packet of seeds in the frig without moistening the seeds, dry cold doesn’t convince them to break dormancy.

Because I’ve never germinated our native hackberry, I looked online to find the length of time the seeds need for a cold treatment. Some people call this treatment cold stratification. I found a couple of different sites that said Celtis reticulata, our hackberry, needs to experience 60-120 days of cold before it will germinate. I also found a recommendation for soaking the seeds for 24 hours. Some seeds, with hard coats, can benefit from this.

After soaking the seeds, I but them into the baggie and labeled it. I try to put the name, date, and how long the seeds need to stay in the frig.

Most people who use this baggie-in-the-frig method add something to the seeds during the process. They put vermiculite or perlite or a little sand in the bag with the seeds. When I first heard about the method I misunderstood the instructions so I’ve done it sans media for 20 some years. It works for me. The theory behind adding perlite to the seeds is to make air spaces around them so that they don’t smother. Funny as it might be to think about, seeds are breathing all the time, even when they’re dry and dormant. My way around the seed suffocation dilemma is to make sure there isn’t too much water in the baggie to start and to check it weekly, open the bag, let air in, make sure the seeds aren’t dry or in standing water. I also use just regular baggies, not freezer bags, so that there is more chance of air getting in and out. I’m describing my method; it might not work for you. With large seeds, like this hackberry, it’s pretty easy. The seeds are big enough that they keep space between them. With smaller seeds, like columbine, it’s trickier. I use a tea strainer to moisten the seeds and then let the water drain away before putting them in the bag.

Each week, as I’m checking on the seeds for moisture, I also look for the first sign of a tiny root. As soon as the root emerges from the seed I plant it in soil. To be clear, as soon as I see a few seeds with roots, I plant all of them in soil. It’s easy to break a root in this process, so I don’t want to wait too long. Usually once a few have germinated the others will not be far behind. The seeds planted in the potting soil are moved to a cool greenhouse where the temperature stays in the 40s at night. Room temperature would probably be okay, too, although there are some persnickity seeds that will go back into dormancy if you raise the temperature too high too soon.

I hope these instructions haven’t scared you away from starting seeds. There are lots of ways to try this on your own. Some home gardeners have good luck with planting the seeds in a pot and leaving the pot outside all winter. Then the seeds germinate when the temperature in nature is right. Whatever method you chose, I urge you to try to germinate some seeds on your own this winter. It’s a thrilling experience the first time you see seeds starting to grow–and it’s still thrilling the hundred-thousandth time, too.